My excruciatingly slow recaps and analyses of Monty Python's Flying Circus now continue where I left off, at approximately the one-third-of-the-way mark of the first(-recorded) episode, "Sex and Violence." We had just gotten a pretty decent example of the latter, with a bunch of small, harmless rodents being musically bashed by large wooden mallets; it only seems right to follow that with an exploration of the subject to the left of the titular ampersand...

(Note: to increase confusion, I am retaining the time-code reference points referring to the YouTube embed of the full episode included in the last post; however, for the purposes of more immediate reference, I am embedding the second ten-minute chunk of the show also available on YouTube in this post. The time codes in parentheses refer to the shorter videos. Got that? Good. Now, please explain it to me...)

10:30 (0:00) - By Python standards, "Marriage Guidance Counsellor" is a rather conventional piece of sketch comedy: a pretty basic premise (couple goes to counsellor out of concern for wife's possible infidelity; counsellor cuckolds husband right in front of him), delivered straightforwardly (at least to a point). With very few changes, the main body of the sketch could have come straight from an old vaudeville show, right down to the trope of a woman getting undressed behind a screen and tossing her clothes over the top of it. (Why a marriage counsellor would have such a screen in his office is never explained; perhaps it's a subtle indication that this isn't the first time he's pulled such shenanigans. Maybe this counsellor's always "on the job" in more ways than one.) Nonetheless, it's still a funny sketch, and noteworthy for the first appearances of two important, erm, figures in the Python universe.

The first is another one of Python's great recurring archetypes: the timid, polite slice of English milquetoast too afraid and unimaginative to make something better of himself, especially if it means causing the slightest ripple in the social fabric, known here (and in at least one other sketch) as Arthur Pewtey. All six of the Pythons had a character (or character type) that captures their personal essence, that couldn't be portrayed by one of the others, and this one is pure Michael Palin.

Palin, of course, is well known as the "nice Python," the one least given to arguing and explosions of bad temper, the one with the seeming inability to say "no." (Which has led to several occasions where he'd quickly agree to one project or another that he would slowly and sheepishly back out of, much to the others' irritation; but, Palin being Palin, no one seems capable of being mad at him for very long.) This may make him the most "English" of the Pythons, and the ideal person to embody the hidden tremble behind the vaunted stiff upper lip. Other than their dental work, the "nice" Englishman may be the hoariest of all Brit-cliches (not to say that it can't be funny, as Eric Idle proves in this highlight - perhaps the only one - from National Lampoon's European Vacation)...

... but Palin, perhaps inadvertently, happened upon a key bit of texture: his underlying passive-aggressiveness. Yes, he's a scared, put-upon little mouse of a cuckold, but his incessant babble barely hides his blinkered self-absorption.

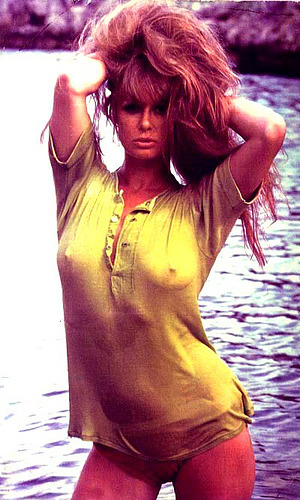

The other important aspect of this sketch is...

...is...

...um, is...

Oh, dear, suddenly I've lost my train of thought and most of the blood in my brain. Must do something...

...ah, much better.

Let us now praise The Seventh Python. Carol Cleveland was originally hired by John Howard Davies (producer - meaning director - of only the first four installments of MPFC before he was replaced by Scots madman Ian MacNaughton from show five on) for only a few appearances, as one of a rotating number of "glamour stooges" to play the female parts on those occasions where it was necessary that they be equipped with, um, female parts. A few other actresses turned up in the early shows, but it soon became clear that only Cleveland had the proper comedic presence to go along with her more obvious attributes, and, by the mid-point of the first series, almost all of the major female roles were hers and hers alone, a confidence that was not misplaced, as she gave invariably fine performances, no matter how insignificant the role.

Good thing, too, because, for all Python's advances in the form, function and subject matter of sketch comedy, they remained rather unsophisticated when it came to what Basil Fawlty called "the contradictory gender." Not that there's any point in singling them out or placing any particular blame on them for it - comedy was no less an overwhelmingly male pursuit than any of the other arts at the time (or indeed most of the rest of society); the increased intelligence and sophistication that informed the sixties comedy boom from Beyond the Fringe on derived from the British educational system, which was either exclusively (boarding/prep school) or predominantly (university) phallocentric. The major targets of the era's satirists - politics, the church, any major societal force you care to name, really - were overwhelmingly male as well. So it follows that the practitioners of the era's comedy - many of whom came out of the same institutions that produced the objects of their ridicule and, if not for fateful moments of redirection, could easily have joined their number - wound up quite naturally both sending up and embodying a point of view that was unusually well-observed, complexly understood, and very, very male.

What women appeared in the major TV and radio comedies of the sixties were either eye candy - little more than curvaceous props placed around the studio for the titillation of their male viewership (and those males involved in their production whose personal preferences weren't as all-male as their public schools) - or strictly performers, so rarely the focus of a sketch that few casts needed more than one. Which is not to say that they lacked talent - the likes of Jo Kendall (I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again) and Denise Coffey (Do Not Adjust Your Set) held their own quite stalwartly among the menfolk surrounding them, and Millicent Martin's presence and singing talent made her the most recognizable member of the That Was The Week That Was team not named David Frost - but their influence on the creative direction of their shows was minimal. (And sometimes even less than that. [The Lovely] Aimi MacDonald was one level a knowing tweak of showbiz convention, including the secondary status accorded to women, but the fact remains that she was completely segregated from the rest of the show with no one to fill the female function elsewhere except for the four writer/performers in drag. Take her links out of At Last the 1948 Show and you'd be left with no women at all.)

In fact, trawl the sixties British comedy waveband, from E.L. Wisty to Arthur "Two-Sheds" Jackson, in search of a strong female voice and you'll come up with a grand total of one: Eleanor Bron. (There originally followed a lengthy exegesis on Ms. Bron that quickly proved too rambling and off-the-point even by my digressive standards. In the interests of maintaining [or establishing] momentum, I've lopped it off and set it aside as a post of its own; this will likely be the next of many such sidebars as this project trundles slowly forward. But for now, let's drop that and move on.)

That MPFC is a male-dominated comedy program is scarcely scandalous, and probably hardly worth mentioning. (To this day, the same can be said for almost all major sketch comedy shows - exceptions like French & Saunders and the short-lived She TV have an understandable but still unfortunate self-segregating quality about them - except, oddly, for the one that had the "boys' club" accusation leveled against it more loudly and frequently than any other. Saturday Night Live was the first sketch show to allow fully-defined female voices to coexist alongside the men; thanks to Lorne Michaels' affinity for a variety of comic tones and his distaste for the homogeneous slurry most TV made of writers' individual contributions, the three female scribes in the early days of the show, while still outnumbered and forced to struggle against sexism both institutional and individual, were able to make distinct imprints on the program. Rosie Shuster [daughter of Frank Shuster of Canadian comedy legends Wayne & Shuster] tended towards absurdism; Anne Beatts brought a more caustic, hard-edged attitude [no surprise, having survived the trial by fire of being National Lampoon's first - and for a long time, only - female editor]; and Marilyn Suzanne Miller [who penned teleplays for Mary Tyler Moore, Rhoda, and Maude, and material for a Michaels-co-produced Lily Tomlin special in 1975] specialized in character studies as poignant as they were funny. I can hardly think of a more convenient encapsulation of the brilliance of these three women than sharing two pieces that ran, side-by-side, on the March 12, 1977 SNL hosted by Sissy Spacek [one of the ten-best episodes in the show's history, sez me]. "Gidget's Disease," by Beatts and Shuster, showcases the full original female cast to delightful effect; Jane Curtin, in particular, gives one of the most hysterical line readings ever. "Young Newlyweds," which follows, may be the best of Marilyn Miller's seriocomic one-act-like sketches, not least because it gives alleged misogynist John Belushi a chance to show off his too-often-underutilized acting chops. Both classics, both very different, and both sketches no man would have written:

Sadly, the sensibility that inspired pieces like "Young Newlyweds" was fairly short-lived on SNL. Jean Doumanian's short, infamous tenure as producer may have set the yin-yuks cause back a few years [though she admirably put a number of Miller-esque sketches on the air that year, several of them quite good]; following the seventh season (for which both Miller and Shuster wrote), the show's tonal variances and most of its experiments were plowed flat, and the gyno-comedic element suffered. Fine female writers clocked in at 30 Rock throughout the eighties and nineties - Pam Norris, Margaret Oberman, Carol Leifer, Bonnie Turner, Christine Zander - and the female performers, most of whom double[d] as uncredited writers, have been consistently strong all along. But it wasn't until the ascendance of Tina Fey to head writer/"Weekend Update" co-anchor in 2000 that the female point of view asserted itself, maybe even dominated, which in turn inspired the present wave of Y-chromosome-deficient writers, performers, stand-ups and podcasters, which may finally have brought us to the promised land where gender parity in comedy has finally been achieved and the only people saying "women aren't funny" are infantile eighty-year-olds and dead Vanity Fair columnists. But that's another digression.)

Python, to their credit, seemed to recognize this gender disparity - later in the season, they made a mini-running gag out of female performers coming on, making a groan-worthy joke, then bursting into tears when the other actors complain, crying "But it's my only line!" - but appeared to have no idea what to do about it, their stabs at enlightenment undercut by regressive attitudes. (Consider Eric Idle: in his term as Footlights President, he made history by unilaterally rescinding the ban on female members; a few years later, when first wife Lyn Ashley made a half-dozen brief appearances on MPFC, she was credited solely as "Mrs. Idle." To complicate things even further, note that that first integrated Footlights cast included future feminist icon Germaine Greer, who herself aroused controversy fairly recently with her own comments on the subject.) Would a female writer have fit into Python? Hard to say, though the one female contribution in Python history - "The Tale of Happy Valley," written for the second Fliegender Zirkus episode by John Cleese and Connie Booth and subsequently adapted for the third Python album and second Python book - is good, and unique, enough to make one wonder what might have been had Booth (who, of course, subsequently proved herself the best collaborator Cleese ever had) been allowed into the fold. (Cleese might have stuck around for the fourth season, at least.**)

But no matter. The Pythons deserve credit for recognizing talent when they see it; Cleveland is featured in thirty of Flying Circus' forty-five half-hours, all of the films and all but one of the record albums, increasingly in roles not pivoting on her pulchritude (even getting a few turns in male drag), and she brings life to even the least of them. The writers' inability to channel a female voice that isn't high-pitched and shrill never quite goes away, of course***, but, as noted, that's a problem shared by even the best comedy troupes and ensembles to this day.**** Cleveland's major roles are few and far between, but, when presented with the opportunity to show her stuff in the non-literal sense, she shines: her hilarious diva fit as Hollywood bimbo Vanilla Hoare in the second series' "Scott of the Antarctic/Sahara" is the high point of that somewhat overlong, meandering sketch. (She also has to lose all her clothing while being pursued by a vicious roll-top desk at the end of it, but this is one case where Python gets to have its cheesecake and eat it too.) And she finally manages a breakthrough of sorts in her last appearance***** in the final true Python project, The Meaning of Life: in the middle of the epic gross-out that is the "Mr. Creosote" sketch, she gets to say this (starting at around 0:14 in the following clip):

** A season in which Booth makes more on-camera appearances - one - than her then-spouse.

*** Their best effort on that score is the character of Judith (Sue Jones-Davies) in Life of Brian, the only female member of the People's Front of Judea (apologies to Idle's Reg/Loretta) and a convincingly proto-feminist figure, a strong-minded woman able to communicate her convictions convincingly even when stark naked in front of the titular pseudo-messiah's mother, a big stride forward in characterization marred only by being the one character in the entire film never given a chance to be funny.

**** The major exception being Canada's Kids in the Hall, an all-male sketch team who took to drag even more than Python but without the slightest undergrad self-consciousness; their many female characters were distinct, well-rounded and brilliantly observed, and often (in their greatest act of subversion) rather attractive.

***** Okay, second-to-last; I just remembered she turns up as the greeter in the hotel-like afterlife at the very end. Don't fuck with my flow, okay? There's an asterisk shortage on.

... which may not seem like much, but to get a (thankfully only verbal) gross-out gag of her own? A highly gender-specific one at that? In the world of Python, that's a Susan B. Anthony moment: equality at last.

(Believe it or not, I haven't even finished analyzing this one sketch, but I'll stop here and pick up again in short order [= less than a year from now]. Stay tuned, Pythonophiles...)

* Admittedly not the most clever subtitle, but the only alternative I could come up with was "Cleveland, Steamer," so consider yourselves lucky.

** A season in which Booth makes more on-camera appearances - one - than her then-spouse.

*** Their best effort on that score is the character of Judith (Sue Jones-Davies) in Life of Brian, the only female member of the People's Front of Judea (apologies to Idle's Reg/Loretta) and a convincingly proto-feminist figure, a strong-minded woman able to communicate her convictions convincingly even when stark naked in front of the titular pseudo-messiah's mother, a big stride forward in characterization marred only by being the one character in the entire film never given a chance to be funny.

**** The major exception being Canada's Kids in the Hall, an all-male sketch team who took to drag even more than Python but without the slightest undergrad self-consciousness; their many female characters were distinct, well-rounded and brilliantly observed, and often (in their greatest act of subversion) rather attractive.

***** Okay, second-to-last; I just remembered she turns up as the greeter in the hotel-like afterlife at the very end. Don't fuck with my flow, okay? There's an asterisk shortage on.

1 comment:

Just stumbled on your blog while looking at some old Python-related stuff. Much too long, but great writing!

"Cleveland, Steamer" is simply too clever and too obscure!

Post a Comment